TRACHEA STENT

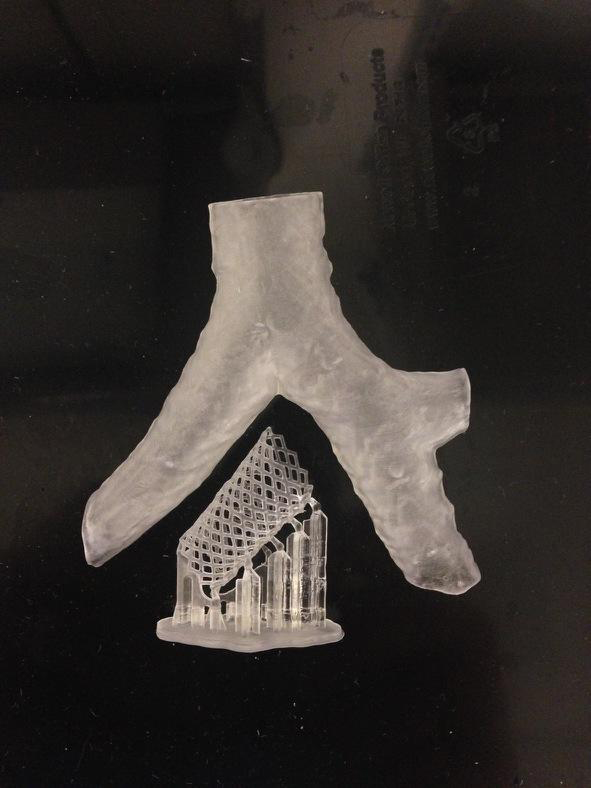

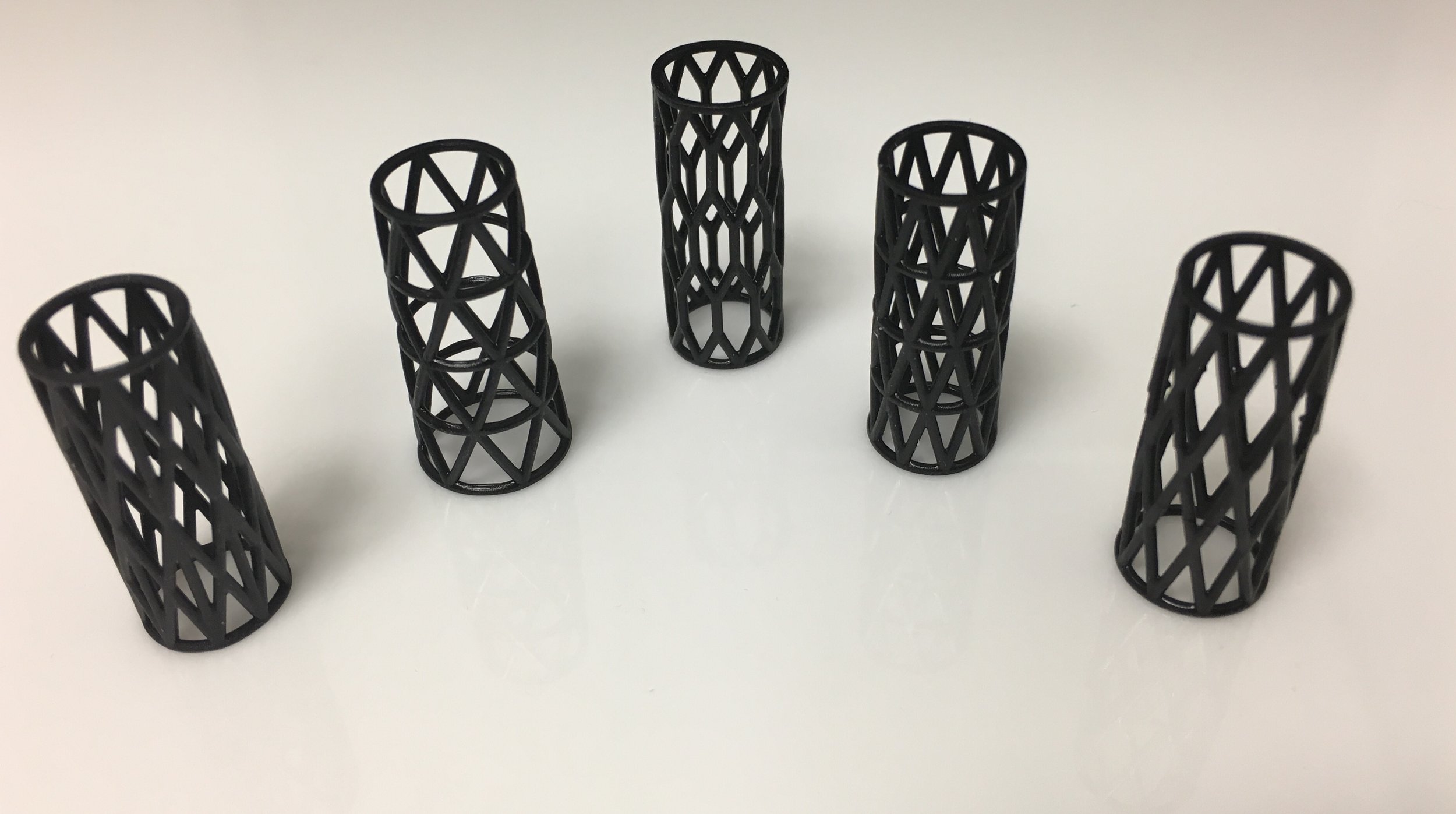

Images from left to right: Current Industry Standard Y-stent, Our 3D printed Stent, Our 3D printed stent in Biocompatible material.

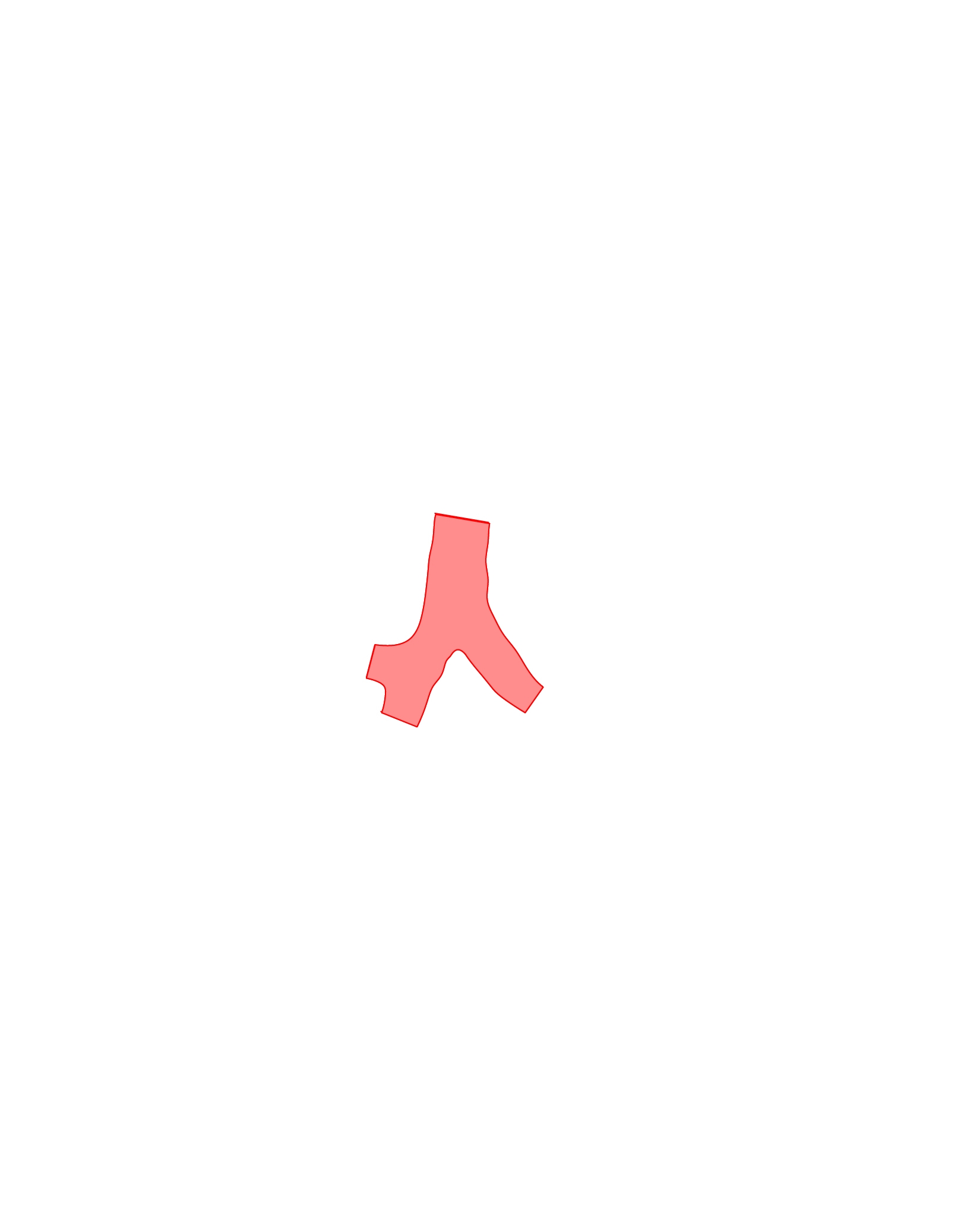

TRACHEA STENTS generated from patient specific CT scans

In collaboration with Dr. George Cheng, Dr. Sebastian Ochoa, Dr. Ken Gall, Dr. Adnan Amajid, et al-- Division of Thoracic Surgery and Interventional Pulmonology, Deaconess Beth Israel Medical Center, Harvard Medical School and Duke University School of Medicine.

As a Lead Biomedical Designer and Researcher on this project, I developed designs using parametric scripts and workflows to generate custom stents based on patient specific CT scan data.

The resulting 'product' of this project is not simply a stent, but rather, it is a set of procedures (an algorithm), which happens to define the parameters for the creation of a custom prosthetic. Form enters a state of latency, resulting in countless manifestations that are not preconceived, yet are predictable. The primary product is a process (a computational set of instructions) which may be realized in physical form once executed. Think of Sol LeWitt's Wall Drawings which exist most purely as a set of instructions, that, once carried out, result in a drawing. The instructions anticipate the form. In this case, the instructions are given as a script and the resulting form is a stent.

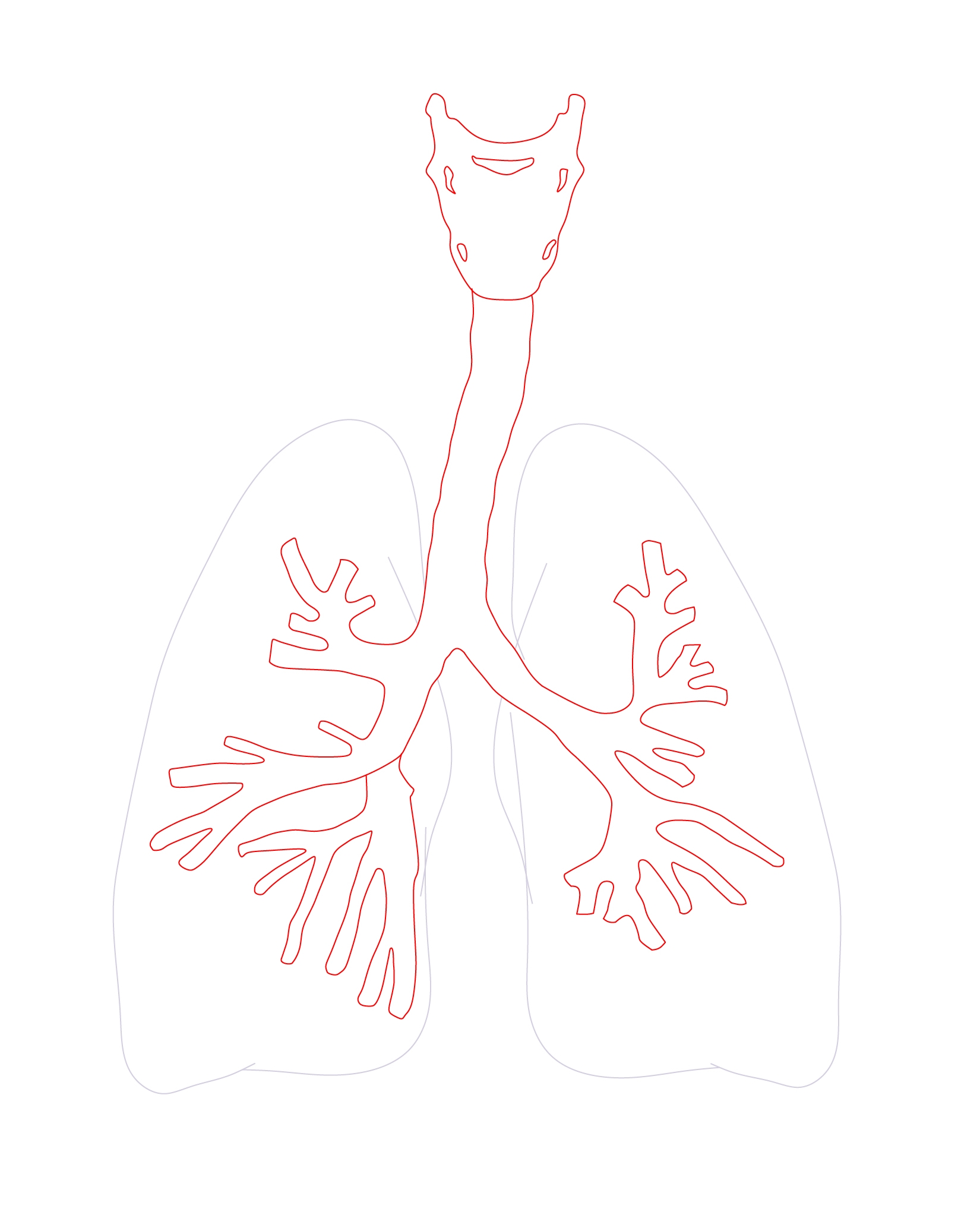

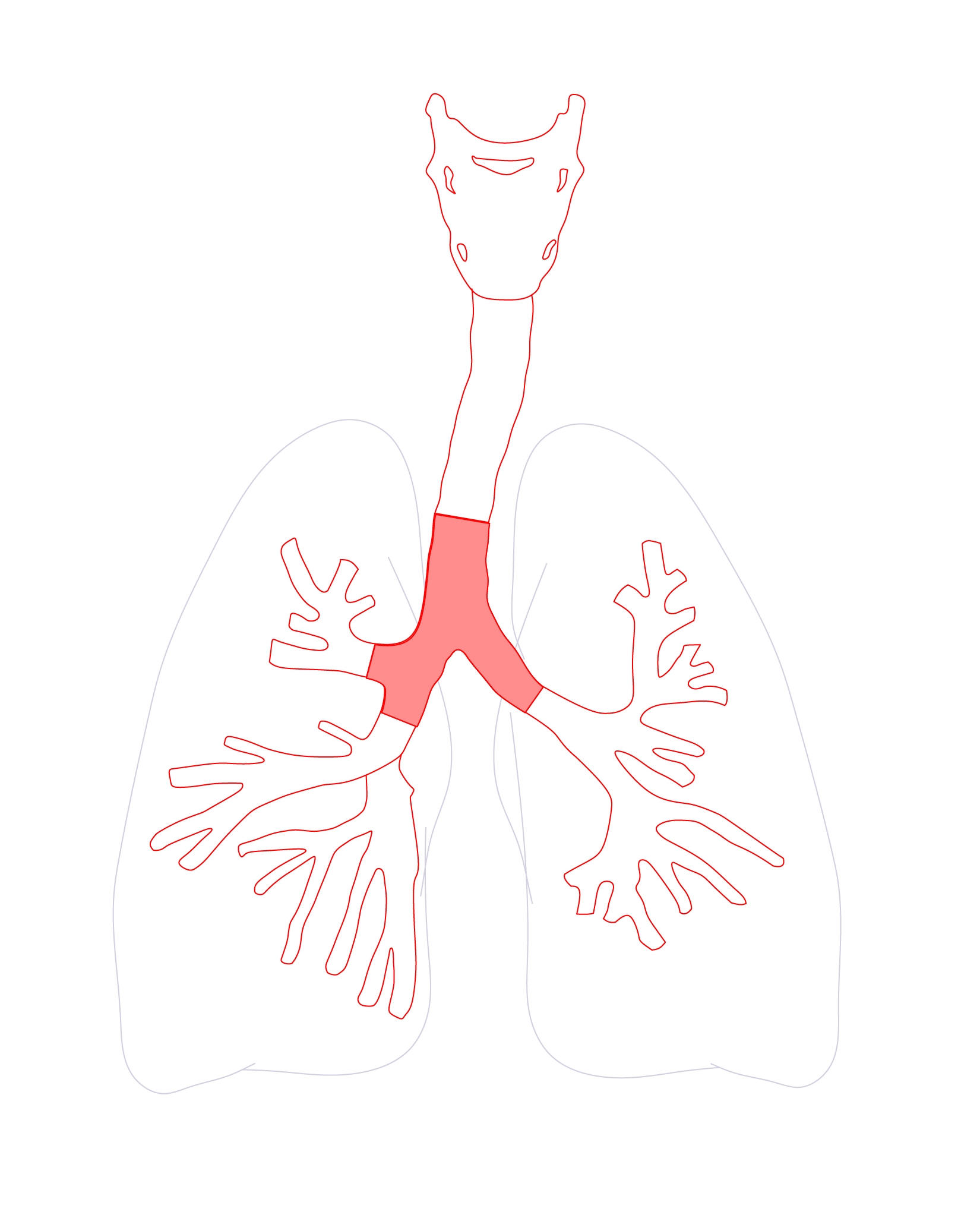

What's a stent and where is the trachea? Good question, at first I didn't know either. After all, my background is in architecture, so how would that prepare me to work in biomedical design and medicine?

As it turns out, designing and modeling a trachea stent isn't very different from how I would create a complex building facade. Both a stent and a facade have an armature, are subjected to similar forces (stress, strain, compression, tension...) and have aesthetic similarities. The main thing separating a stent armature from being a building armature is a change in scale. A stent is roughly 30mm tall while a building is upwards of 30m tall. When it comes to modeling these forms in vector space, size is irrelevant.

The stent inhabits the body, but if scaled up +1000 times, it could serve as inhabitation for the body.

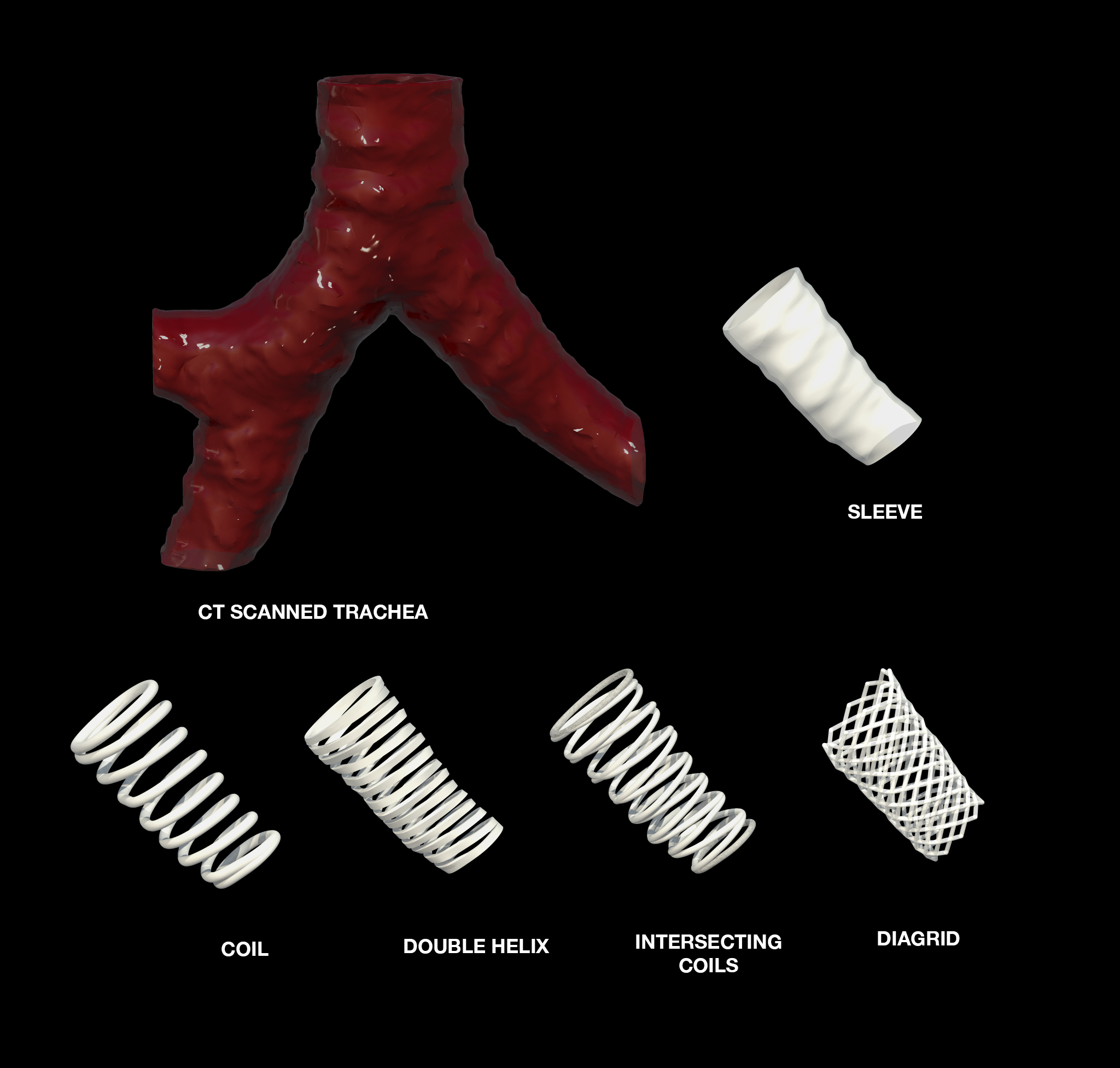

We began with a CT scan of a patient's trachea.

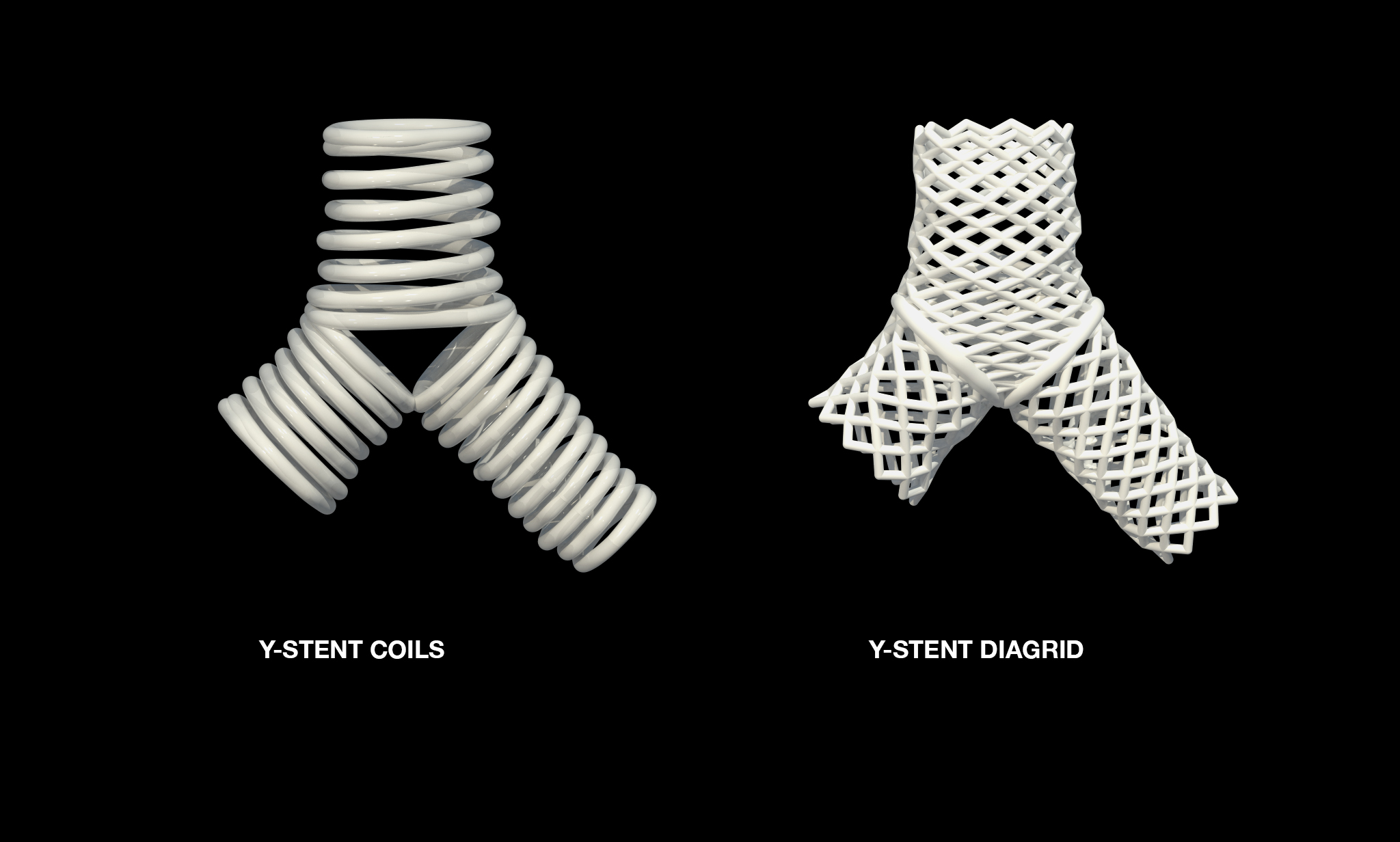

After I established a way to isolate the inner airway, I began mapping a range of different patterns and mesh densities to the form.

Once a script was developed, we were to rapidly create stents that were perfectly fit to a patient's anatomy.

The engineers, artists and architects on our team are primarily experienced in digital computation for architectural and sculptural design. The clinicians, on the other hand, are experienced with producing 3D models from CT scanners. By bringing together these two worlds of art and science, we are able to achieve significant 3D modeling possibilities.

Currently, we are analyzing a full range of forms with different densities using custom biocompatible materials to determine which design is best suited to be a stent. Stay tuned...

For more info see:

George Cheng, Erik Folch, Noah Garcia et al., 2017, Pulmonary Therapy, 3D printing and Personalized Airway Stents, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41030-016-0026-y